Kurdish language policy of Iran

Kurdish language policy of Iran

State Policy of the Kurdish language: The politics of Status Planning

The Pahlavi dynasty, 1925-1979. The first constitution of Iran, adopted in 1906, made Persian the only official language of the multilingual country.

State Policy of the Kurdish language: The politics of Status Planning

The Pahlavi dynasty, 1925-1979. The first constitution of Iran, adopted in 1906, made Persian the only official language of the multilingual country. Although this may be considered the beginning of an official language policy reflecting the position of Persian nationalists it was not until the coming to power of the Pahlavi dynasty that the central government was in a position to implement the constitutional stipulation effectively.

The Pahlavi dynasty was established by Reza Khan who came to power through a coup d’etat in 1921, and declared himself the King of Persia (1925-41). Like Kemal Ataturk in Turkey, he inherited a loosely integrated state and aimed at setting up a highly centralised system of political rule. The integration of the country’s ethnic peoples (numbering about 50% of the total population) was carried out by among other coercive measures, the exclusive use of the Persian language in education, administration, and the mass media.

As early as 1923, the government offices were instructed to use Persian in all their oral and written communication. A circular sent from the Central Office of Education of Azerbaijan Province to the education offices of the region including that of Saujbolagh (later renamed Mahabad) reads: On the orders of the Prime Minister it has been prescribed to introduce the Persian language in all the provinces especially in the schools. You may therefore notify all the schools under your jurisdiction to fully abide by thus and to conduct all their affairs in the Persian language… and the members of your office must follow the same while talking (reprinted in Girzey Kurdistan, Vol. 2, No. 6. 1981, p. 34). With the consolidation of his power, Reza Shah moved to ban all Kurdish cultural traditions, dress, literature, music and dance. The contemporary poet Hemin (1972:6) recalled that “thousands of Kurds in schools and offices and even in the street were arrested, tortured and disgraced on charges of speaking in Kurdish…” The horror of police surveillance had a devastating impact on the language. In bis autobiography, poet Hazhar (1968:154-55) wrote that he and his father had put their few Kurdish books in a metal box and buried it in the courtyard in their village house which was far from the closest city. They read the books only during the night and buried them a8ain. Another poet, Khala Min, read his poems only to his closest friends, and to make sure that it does not appear in writing, the poet himself had to memorise the poem. Greatly affected by one of his poems when read by a friend of Khala Min in a private gathering of the village mosque school, young Hazhar walked a distance of three days to Mahabad to ask for his poetry. The poet denied that he had ever composed any poems (ibid., p. 155f).

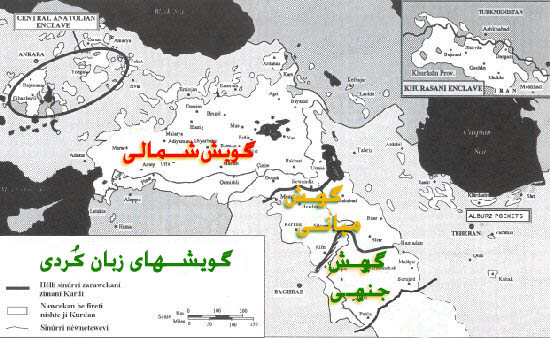

To prevent the consolidation of the Kurds as a nation, the new administrative system cut across the Kurdish speech area dividing it into three provinces directly attached to Tehran. Efforts to eliminate the Kurdish ethnic identity were extended beyond the borders of the country. The Lutheran Orient Mission which had been operating in Saujbolaq area (at that time part of Azerbaijan province) was forced to remove the name Kurdistan from its monthly English language journal, Kurdistan Missionary.

The abdication of Reza Shah in 1941 brought some relaxation of coercive assimilation though Persianisation was continued by Mohammed Reza Shah (1941-79). The Kurds were now considered to be “true-born (asil) Aryans,” although their language was called a “dialect” in all official pronouncements. Under the favourable conditions of the post-World War 11 years, the Kurds and Turks of north-western Iran established their own autonomous republics in 1946 and made Kurdish and Turkish official languages of their states.

When the Imperial Iranian Army attacked and toppled the republics, all the written records were destroyed. In Tabriz, Turkish books were piled up in front of the Municipality building and set on fire by government officials (Ettela’at, December 18, 1946).

Ideologically, the assimilation of non-Persian nationalities was based on the glorification of Iran’s pre-lslamic past and the “Aryan race” to which Iranians were claimed to belong. The political and linguistic aspects of the official Line found immediate support among Persian nationalists who went to extremes in order to legitimise the assimilation policy.

Commenting on the dangers of the independence movement of the Kurds of Turkey, Mahmud Afshar, editor of the magazine Ayanda proposed a program for assimilating the Kurds. “Whenever this course, ie, Persianisation (farsi shudan) of the Iranian Kurds is achieved, there will be no danger to us if Ottoman Kurdistan becomes independent” (Ayanda, Vol. 1, No. 1,1925, p. 62).

Members of the faculty at Tehran University and elsewhere also supported the Persianisation policy by claiming that Persian was the most exalted language of the world and the only language in Iran. M. Moghadam (Tehran University), for example, tried to prove that Turkish was a Persian dialect (Doerfer 1970:224).

When census figures on the languages of Iran were released for the first time in 1960, the Tehran daily Kayhan carried interviews with three philologists one of whom, S. Kiya, claimed that there was only one language in Iran (February 7, 1960). Another authority, Dr. Safa, said that with the exception of some Turkish “dialects” which had “regretfully” become the speech of some Iranians, all other dialects had “Iranian roots” (February 10, 1960).

In the late 1960s, the Ministry of Culture and Arts commissioned three experts, two of them linguists from Tehran University, to pre-pare reports on the “strengthening and spreading (taqviyat va gustarish) of the Persian language.” One of them, M.R. Bateni (1970:69-63), considered Persianisation “an important step toward national unity” though he reminded his readers that “material welfare and political and economic development of the country” were equally important factors in pre-venting “secessionism”.

While the Ministry of Culture and Arts was engaged in finding out about the linguistic assimilation of non-Persian peoples, there is evidence suggesting that the Iranian regime was considering plans for the transfer of the Kurdish population to non-Kurdish areas of the country.

In spite of the obvious de-ethnisation policy, the last Pahlavi monarch applied his “safety valve” approach to the Kurds whenever the government was weak or threatened. Thus, during the 1941-53 period, when the central government was vulnerable, pressure on the opposition including the Kurds was occasion-ally relaxed. Two Persian language periodicals, weekly Kurdistan (The Highlands, 1945-60) and Mad (Media, 2 issues 1945) launched by Kurdish editors/publishers appeared in Tehran. The former reported on the problems and grievances of the Kurdish provinces and carried articles on Kurdish history and literature including poetry in Kurdish. The latter was a Kurdish studies journal. The government itself published Baghistan (one issue, Azar, 1331/1952, subtitled Historical and Cultural Studies of the Kurdish-inhabited Regions monthly publication of the General Office of Publications and Propaganda, in Persian and Kurdish Languages) under conditions of resurgence of Kurdish nationalism.

Even when the Shah was in firm control of the country in the post-1953 period, potential developments in the region were responded to by, among other things, military and political, measures, the initiation and expansion of Kurdish broadcasting, limited publishing in the Kurdish language and even the offering of two courses on the Kurdish language by the Department of Linguistics of Tehran University.

THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN

The Kurds participated in the anti-monarchy revolution of 1978-9 actively and raised demands for autonomy within a federally organised democratic state. A major feature of this proposed system of self-rule would have been the officialisation of the language, ie its use in education, local administration, and the mass media. (2) These demands were not, however, compatible with the centralised theocratic regime that was bein8 established by the new rulers who chose to Islamicise the state system which they had inherited. Thus, within two months after the overthrow of the monarchy, the Islamic Army was mobilised against the autonomy-seeking peoples, the Kurds, Turkomans, and Arabs.

The new constitution adopted in December, 1979, sanctions the centralisation of political, economic, administrative and cultural life of the country as had been practised by the Pahlavi state during the climax of monarchial power. (3) State control of the economy includes oil and other major mineral resources, transportation, large industries, banking, foreign trade, energy, etc. (Article 44). Governors from the highest rank (province) to the lowest (rural areas) are appointed from the center (Article 103). Although political organisations are allowed to operate (Article 26), the ruling Islamic Republic Party was the only one able to function openly. Moreover, the ownership and operation of the influential broadcast media is the prerogative of the state (Article 175).

The more obvious contrasts between the old and the new regimes is in the sphere of ideology. A particular brand of Shiism is the official religion (Articles l and 2), and the state is responsible for propagating this sect and its Persian-based religious culture in Iran and out-side the country (Preamble). The Islamic state’s approach to the multilingual and multicultural nature of the country is, with minor differences, a continuation of the old regime’s policy. According to Article 19 of the Constitution, ‘colour, race, language and the like shall not be cause for privilege.” (4) The privilege of official status is, however, granted only to Persian, the native tongue of no more than 50% of the country’ s population. According to Article 15, The official and common language and script of the people of Iran is Persian. Official documents, correspondence and statements, as well as textbooks, shall be written in this language and script. However, the use of local and ethnic languages in the press and mass media is allowed. The teaching of ethnic literature in the school, together with Persian language instruction, is also permitted (ibid., pp. 22-23). Thus, education and administration in the native tongue is not allowed for the non-Persians. the teaching of “ethnic literature” in Kurdish or in other languages had not been allowed by the mid-1980s. Broadcasting has, however, continued along the lines drawn by the former regime while publishing, both state sponsored and private, is much more expansive.

The Islamic constitution differs from its predecessor in officialising the “Persian script”, which is the Arabic alphabet with the addition of four Persian letters formed by the use of diacritical marks. Reflecting the Islamic bias of the regime, this is apparently aimed at preventing any move towards Romanisation of the alphabet as was carried out in Turkey. It also implies that the Kurds of Iran cannot opt for the unification of the Kurdish alphabet on the basis of the Roman and Cyrillic alphabets which are currently used by Kurds in other countries. The Islamic regime, is however, currently using the Roman Kurdish alphabet for propaganda purposes.

The rather relaxed policy on the use of Kurdish in broadcast and print media can be explained by the political situation prevailing in Kurdistan and the region. The new rulers had virtually no effective control over Kurdistan after they came to power. To win the “hearts and minds” of the secular nationalist Kurds, who were audiences to the media output of the autonomist organisations based in the “liberated areas,” the government had to communicate with them in their own language. Another impetus is the regimes, expansionist schemes, the avowed “export of the Islamic revolution”, especially to Iraq where an armed autonomist movement was active since 1961. In fact to weaken or, ideally, replace the nationalist forces the government went as far as creating its own “Muslim Kurdish” parties and armed groups (see Van Bruinessen 1986:29-24).

To promote the official brand of Shiism among the predominantly Sunnite Kurds, the Islamic regime has opened government controlled religious schools (eg in Paveh) and has published translations of Shiite religious works into Kurdish. The bimonthly Armanc, organ of the Islamic Propagation Organisation, has even devoted a few pages to propaganda in Kurmanji and in the Roman script for the Kurds of Turkey. Although the Islamic leaders regularly renounce nationalism of any sort as “evil” and “Western”, their approach to the non-Persian peoples of Iran has rarely deviated from the Persian “national chauvinism” openly espoused by Pahlavi monarchs. On the strength of the evidence presented in this study, it seems that assimilation has been the cornerstone of the language policy of both monarchical and Islamic regimes. The flexibility demonstrated since the 1950s (in broadcasting and publishing) has, pragmatically, served the overall assimilation policy rather than maintaining the linguistic and ethnic identity of the Kurds.

NOTES

- Even before the fall of the Qajar dynasty (1779-1925), Mohammad Ali Foroughi, representative of Iran at the League of Nations, sent the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at Tahran a confidential report (1920) on the discussion of the Kurdish question at the League and presented his own assessment of the 44dangers~<^ of the independence of the Kurds of Ottoman Turkey. To integrate the “minorities, he advised his government to avoid coercion and to propagate the Persian language, literature and culture.He noted that there was no need to make speaking in Persian compulsory “By lucky chance he wrote, “neither Turkish nor Kurdish is a literary language and our minorities do not have literary and cultural capability (maya) and they will be easily absorbed (mustahlak) in the Persian language, literature and culture” (extract of the text in Yaghma, vol. 3, No. 7, Mehr 1329/Sept-Oct 1950, p.266).

- Detailed information on the demands of the nationalities of Iran in the post-1979 period is found in the Iranian press of 1979-1980 especially in Baltan-i Showra-yi Hambastasi-yi Khaltl ha-yi Iran (Bulletin of the Solidarity Council of the Peoples of Iran), Tehran, 1979-80 and Azadi, published by the National Democratic Front in Tehran, 1979-80.

- For a comparative survey of the two state systems especially in connection with the integration of ethnic and religious minorities of. Higgins (1984).

- Constitutions of the Countries of the World, Iran. April 1980. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana Publications, p 24.