Don’t you think the borrowed letter [ḥ: ح] which is very commonly in use needs a representation?

Don’t you think the borrowed letter [ḥ: ح] which is very commonly in use needs a representation?

Don’t you think the borrowed letter [ḥ: ح] which is very commonly in use needs a representation?

Many words have been borrowed into Kurdish without being Kurdified, as Kurdish never had rules for these sort of activities. Some of these words have found home in the Kurdish language and people learned to pronounce them exactly as the native language. However, this is not widely accepted and only certain sub-dialects are able to practice it. These loanwords largely borrowed from Semitic languages often contained phonemes which were not represented in Kurdish as an Indo-Iranic language, such as [ḥ: ح].

Many words have been borrowed into Kurdish without being Kurdified, as Kurdish never had rules for these sort of activities. Some of these words have found home in the Kurdish language and people learned to pronounce them exactly as the native language. However, this is not widely accepted and only certain sub-dialects are able to practice it. These loanwords largely borrowed from Semitic languages often contained phonemes which were not represented in Kurdish as an Indo-Iranic language, such as [ḥ: ح].

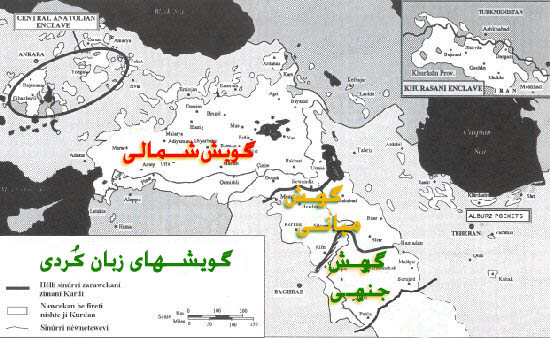

The guidelines for creating a new writing system for Kurdish in a wider perspective allows us to accept some practical justifications to enable Kurdish writing across all dialects with a workable solution. Based on this rule, nothing will stop a person from Cemcemall to still write “Heya”, and read [Ḥeya] or a person in Kirmanshan write “Heya”, and read [Heya] as a local dialect justification. We have these exceptions in all languages. Representation of too many exceptions in the Unified system will lead to an unfeasible alphabet system.

You might be familiar with the English language and its variety of dialects. The same word like “Here” is read so many different ways by a Scottish, Irish, Hindi, Jamaican, American and a Londoner, but it is still written that way. Heya, Hukúmet, Hurríyet, Hellqe, Hereket (Awrú, Komar, Azadí, Zenjíre, Júlanewe) can follow Kurdish spelling standards but pronounced in a different way in a different area. If you look at the word “Heft” (H’eft in Silémaní, E’ft in Hewlér), “Ehmed ” (EH’med in Silémaní, E’med in Hewlér), and how it differs in each part of Kurdistan then you realise that you need to have rules regarding how a word is written down in a standard way.

Another imortant factor is the level of usefulness of these common loan phonemes in modern Kurdish versus the 1920s and 30s. At KAL’s image gallery, samples of writing from famous historical figures are provided to allow for easy comparison of the development of various writing styles. These personalities were among the most lettered Kurds of their time. A majority of the pioneering Kurdish writers were well versed in the dominate lingua franca of their time and locale, such as Arabic, Persian or Ottoman-Turkish. The devised Perso-Arabic writing system for Kurdish of the 1920s was a direct response to common literacy in Arabic, Persian and Ottoman-Turkish. The Arabic alphabet was the shared base for writing Persian, Ottoman-Turkish and naturally, the newly devised Kurdish of the 1920s.

The writing and pronunciation of Arabic loanwords by Kurdish speakers were diverged, as it is today. In some domains, political and religious centres of 1920s such as Silémaní and Koye, the codification movements were initiated, the importing of Arabic phonemes as it was written and pronounced in Arabic were a natural course. These writing practices of Arabic loanwords was carbon copied from Persian and Ottoman-Turkish writing experiences.

Today the Yekgirtú (Yekgirtí, Yekgirig) Unified writing system for Kurdish needs to cover many modern factors that dominate the communication and lifestyle of modern Kurdish speakers as well as practical usability of the system in a wider Kurdistan. Yekgirtúbestows the Kurdish language with a new horizon of growth in the 21st century.