RECENT NEWS

28/08/2018

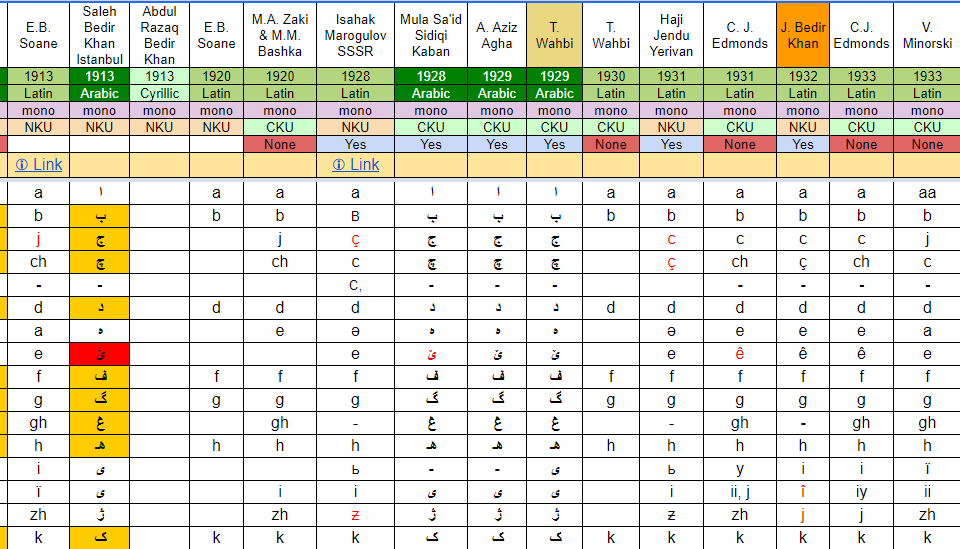

No they will not. In contrary with the framework for previous successor of Kurdish orthography by legends like J. Bedir Xan and T. Wehbí whom considered […]

28/08/2018

The Kurdish language is vibrant and multi-dialectic and has one of the richest oral literature traditions in the world. A unified writing and scripting system will […]

28/08/2018

There are several meaningful ways for individuals and organizations to get involved with projects, such as the Kurdish Academy of Languages (KAL) and KURDISTANICA. These projects […]

28/08/2018

Language is the vehicle that we commonly use to exchange ideas in our shared environment. In short, language is one of the keys that unlock the […]

28/08/2018

چرا زبان از اهمیت ویژه ای برخوردار است؟ Sat, 12/06/2010 – 15:55 — Admin زبان وسیله تبادل افکار و همچنین یکی از کلیدهای گشودن قفل ذهن […]

NEWLY POSTED

10/04/2011

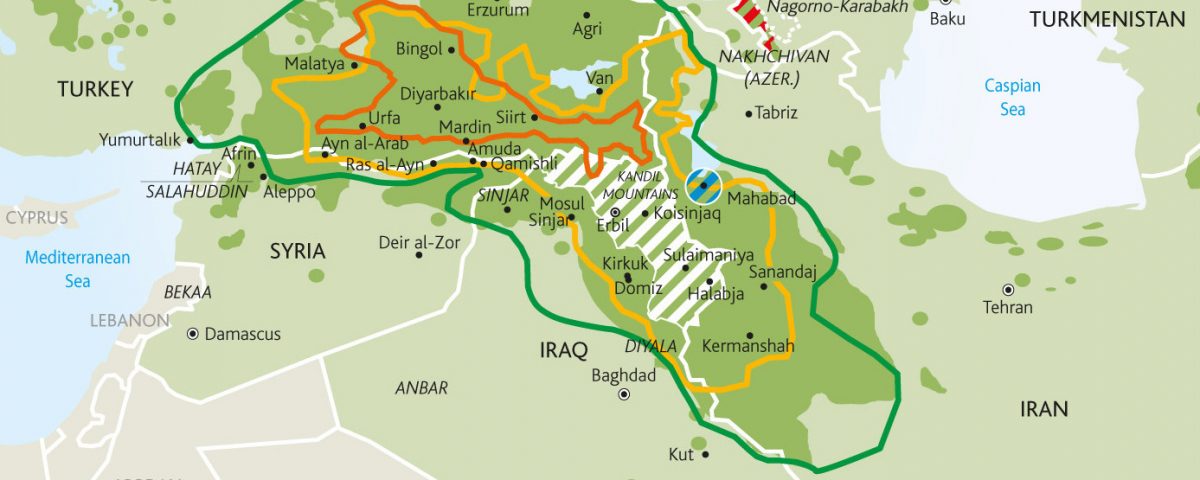

The unprejudiced academics that study Kurdish history are united in the view that the Kurds are an ancient race (1). The Kurds have lived for many […]

11/03/2011

Modern formal schooling, which is usually structured in the form of primary, secondary and higher education, relies on the extensive use of written and oral […]

06/12/2010

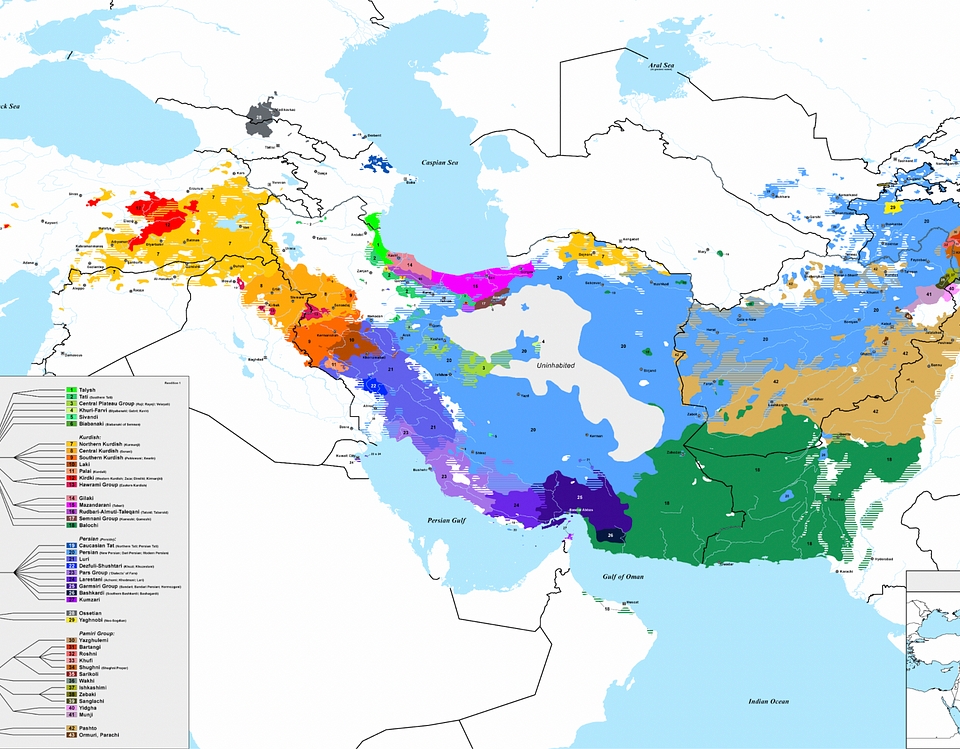

Kurdish (Kurdish: Kurdí, كوردی, Kurdî, Кöрди) language belongs to the Indo-European family of languages. Kurdish dialects are members of the northwestern subdivision of the Indo-Iranic language, […]

19/08/2010

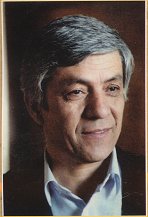

Dr. Ali Rokhzadi (Kurdish: Elí Ruxzadí, علی روخزادی) was born in 1946 in the small village of Xalle Waze in vicinity of Xurr Xurre area of […]

25/09/2009

History of Kurdish language: Articles Section for related Articles on historical perspective of Kurdish language Ibn Khallikan’s Biographical Dictionary The Language of the Medians The origions […]

HIGHLIGHTS

Linguistic Figures

19/08/2010

Dr. Ali Rokhzadi (Kurdish: Elí Ruxzadí, علی روخزادی) was born in 1946 in the small village of Xalle Waze in vicinity of Xurr Xurre area of […]