Lexical Modernization

Lexical Modernization

Modernization has embraced all aspects of vocabulary, although it can be traced more conveniently in the specialized lexicons or, to use a more appropriate term, registers that have evolved especially since the 1920s. A “register” is a variety of language defined according to its use in special social situations. In Hallidayan linguistics, it is a variety characterized “according to use.’ It is distinguished from regional or social dialects, which are varieties defined according to the characteristics of the user. According to Halliday (1976:5-6), the existence of social dialects reflects the hierarchical form of the social structure. The existence of registers reflects the variety of human roles and actions and, in particular, the social division of labor.

A. Early Registers

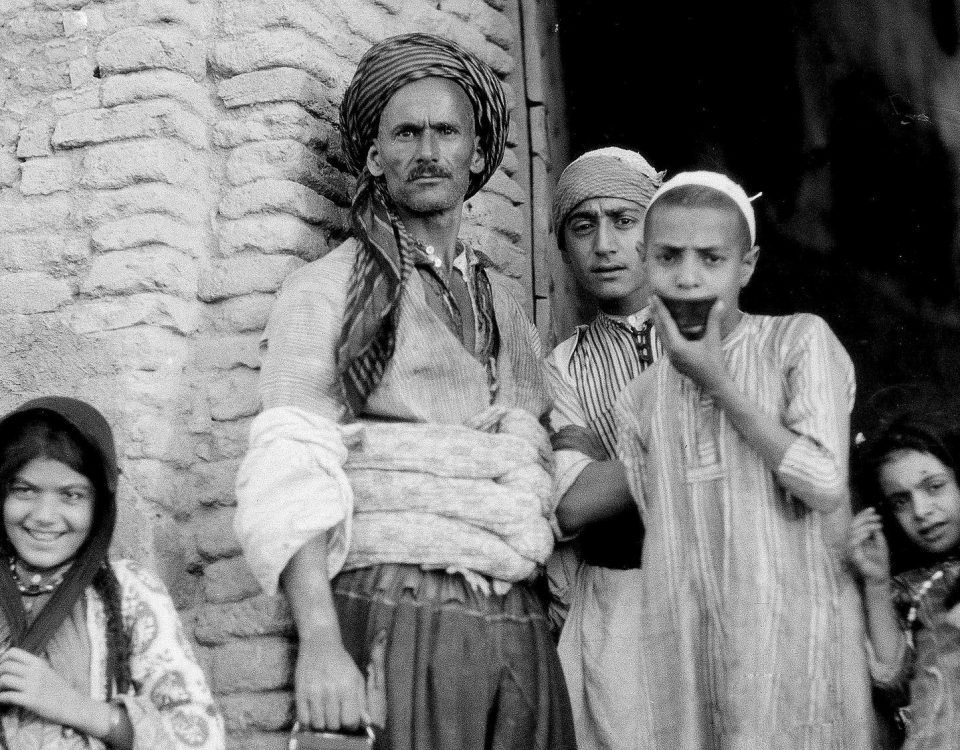

Throughout the centuries, specialization in knowledge and experience evolved throughout the centuries in the agrarian society of Kurdistan and was transmitted from generation to generation through the use of terminologies appropriate to each area of expertise. These terms were created and/or borrowed by illiterate farmers and artisans who taught their apprentices informally and on the spot.

The primitive registers, often pejoratively called “jargons,” are small in size and extensively overlap with non-specialized vocabulary. For example, the water mill has provided a register of at least 96 terms arid no less than 13 proverbs and proverbial phrases (figures calculated from terms collected by Fattahi Qazi 1972; 1972a). Baking bread, traditionally a female household activity, has furnished about 95 terms and 21 proverbial phrases and idiomatic expressions mostly based on the word nan ‘bread’ (cf. collected terms in Fattahi Qazi 1973). The primitive loom, still popular in Kurdistan, provides 86 terms and twelve idiomatic expressions (cf. terms collected by Fattahi Qazi 1983). The only dictionary of agriculture (Qaradaghi 1972) which includes also the registers of non-agricultural crafts lists some 7,000 items selected from (lie compiler’s unpublished general dictionary of 30,000 words. Thus, agricultural terms make up about 23% of the general vocabulary of Kurdish.

In the intellectual field, religion and literature each developed registers that draw heavily on Arabic and Persian. Islam’s prohibition on the translation of the Koran and the obligatory use of Arabic in prayer and other religious rites have likely contributed to the limited size of the religious lexicon. The more abstract and specialized terms in theology and jurisprudence are, thus, Arabic loanwords and limited in usage to the clergy. In the more practical domains most of the terms are of native coinage, e.g., nöj (kirdin) ‘(conduct) ritual prayer’, niwéjjí beyan, níwro, éware, shéwa, xewtinan ‘morning, noon, afternoon, evening, night prayer’, de nöjî ‘minor ritual ablution’, bredeniwéjh ‘slab reserved as place of niwéjh’, rojhú girtin ‘to fast’, bang ‘call to niwéjh’ and many more. In the realm of literature, poetry has furnished a more extensive stock of native and borrowed words.

B. New Registers

Against this background, new registers of administration and law, elementary science, the humanities and social sciences developed after 1918, primarily as a result of officialization of the language, i.e., its use in education, mass media and administration. Unlike the Western industrial societies, these registers were not a product of a new, social and geographical division of labor within Kurdish society, although processes of social and economic development became a contributing factor later.

Borrowing from Arabic, Persian and Turkish was at the beginning the main source for providing new terms. Gradually, however, the borrowed terms were purified, and new terms were coined, as is illustrated by the following examples from two selected fields.

Administration. The administrative use of the language (cf. 7.6.0) has furnished both a register and style of official correspondence and advertising. The following are examples of the old loan-terms (Arabic words in Kurdish pronunciation) and their new equivalents (some of the coinages include loan elements, e.g., serbaz and quttib):

Loanwords

| idare belediye te’sîs difa’ re’îs ‘erîze mu’esker medrese terbiye cami’e dar cimhûtrî |

‘(to) administer’ ‘municipality’ ‘(to) found, institute’ ‘defence’ ‘chief, head’ ‘petition, complaint’ ‘garrison’ ‘school’ ‘education’ ‘university’ ‘house, office’ ‘republic’ |

berréwebirdin sharewaní damezrandin bergirí serok skallaname serbazge qutabxane perwerde zanistga dezga komar |

The terms are mostly lexicalized and used in the press, official correspondence and broadcasting.

Science. The early scientific terms of school texts are dealt with in 7.5.5.3. Besides secondary school textbooks translated in the 1970s and early 1980s, the Kurdish Academy’s terminologies (cf. 7.6.1) provide hundreds of coinages that have yet to find application, e.g.:

| ashqeawí rarrewí gerrokayetí reseneceshn diyardeceshn mezeceshn tozkallekí rengkörí ronaneweyi Azmúní Tékxistinewey Mínesota |

ablutomania peripateticism genotypes phenotypes temperamental types molecular achromatopsia metabolic Minnesota Mechanical Assembly Test |

One outlet for terminological creation and usage in the 1980s is the popular scientific articles written and or translated in the Iraqi journals Roshinbírí No and Karwan (cf. 7.6.1). The following terms, for example, were coined by the writer of an article on “The Glacial Age Man” (Roshinbírí No, No. 111, 1986:43-63):

| Caxí Bestellek Serdemíi Baraní Mezin Miroví ballarrék |

Glacial Stage Great Interglacial Age Homo erectus |

The writer of an article entitled “Laser and Maser” (Karwan, No. 44, 1986, 68-74) has coined the following terms:

| shebeng girdíle banwenewsheyí neayonraw tíshkí binsúr gewrandiní tav |

spectra atom ultraviolet deionized infrared radiation light amplification |

These popular science articles number around twenty per year. Although dictionaries of scientific terms have appeared (cf. 8.4.5), the absence of college level education and textbooks is a prohibitive factor.

C. The Problem of Lexicalization

Which terms get general acceptance and become part of the vocabulary?

Lexicalized terms happen to belong to registers that have been frequently used; they include neologisms in domains such as politics, literary criticism, grammar and administration. Many of these terms are already part of the active vocabulary of those who are literates, especially in their writing.

Grammatical terms provide an example of the lexicalization process. Reviewing three grammatical studies published in Kurmanji and Sorani in 1956, Bois (1960) demonstrated enormous chaos in terminology. Two decades later, we find a striking degree of unification of new terms, coined mostly on the basis of English terminologies rather than traditional loans from Arabic. The following examples are popular coinages:

| réziman naw awellnaw kirdar awellkirdar bizwén téperr téneperr pashgir péshgir lékdiraw nawgir héz dengejé |

‘grammar’ (ré- ‘road’ + ziman ‘language’) ‘noun’ (native word for ‘name’) ‘adjective’ (awell ‘companion’ + naw ‘noun’) ‘verb’ (native word for ‘actin, deed’) ‘verb” (awell + kirdar) ‘vowel’ ‘transitive’ ‘intransitive’ ‘suffix’ ‘prefix’ ‘compound’ ‘infix’ ‘stress’ ‘vocal cords’ |

Political science terms have also been lexicalized due to their frequent use in the press and broadcasting, e.g.:

| rékxistin bizútinewe cín xebatí cínayetí rébazí siyasí néwneteweyí fireneteweyí |

‘to organize’ ‘movement’ ‘class’ ‘class struggle’ ‘political line’ ‘international ‘ ‘multinational’ |

Obviously, usage is largely determined by extralinguistic factors. Kurdish, like other “modernizing” languages, is capable of developing large stocks of terms while continuing to have lexicalization problems. Some of the more advanced South Asian languages provide a similar experience. Malay, for example, created some 71,000 terms in ten years, while about 350,000 technical terms were collected for Hindi. Similar stocks were also provided for Tamil, Telugu and other languages. Social and political obstacles do, however, prevent their effective use (Maloney 1978:12-14). Non-linguistic limitations on the use of terms in Kurdish are examined in 7.6.1.

Source: Prof. A. Hassanpour, Nationalism and Language in Kurdistan 1918 – 1985