Lexical Purification

Lexical Purification

To many Kurds, the most visible feature of the standard norm is its purified vocabulary in both prose and poetry which, compared with the 46.4% loan load of the 1920s-1930s, carried only 4.4% in the 1960s (cf. Table 57).

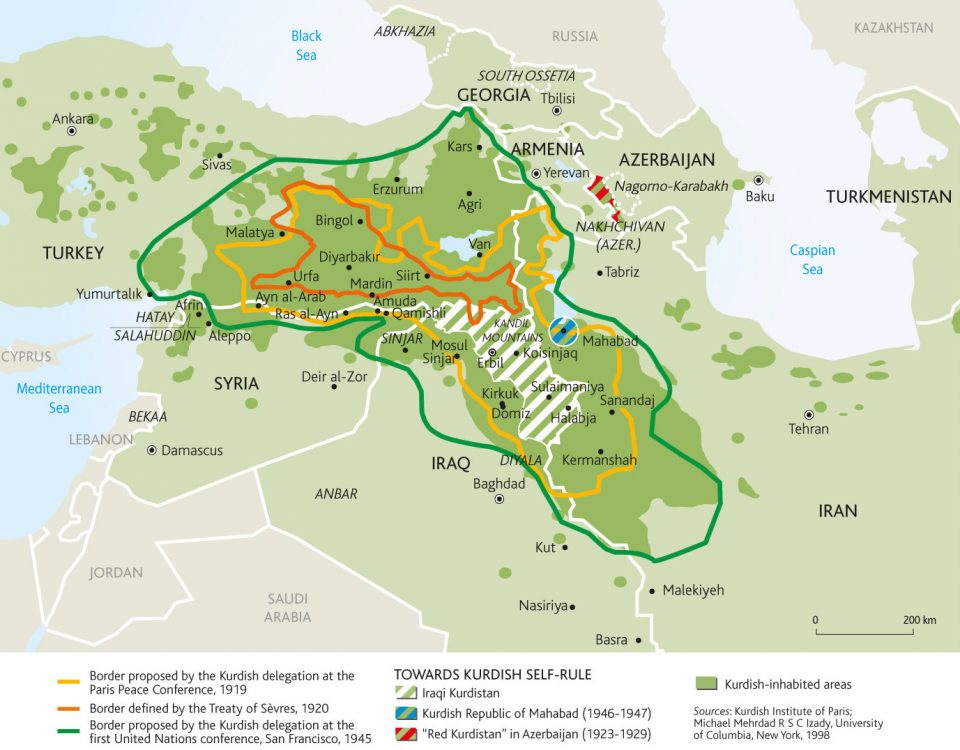

The Foreign Element. Kurdish has been in contact with several languages and has been enriched by borrowings throughout the centuries. There has been intensive interaction with Arabic, Persian, and Turkish as the official languages of states ruling over Kurdistan, as neighbouring languages and, in the case of Arabic, as the language of a common religion. Armenian and Assyrian, both neighbouring languages, have also affected the Kurdish language, especially the Kurmanji dialect (cf. Map 1).

In the absence of etymological studies, it is not possible to calculate the ratio of native elements to loanwords that are in general use or fully nativized. A rough idea may be gained, however, from borrowings marked in Wahby and Edmonds’ (1966) dictionary (calculations are of author):

| Native Words Loanwords Arabic European Persian Turkish Total |

5,896(86.1%) 945 (13.8%) 716 (10.4%) 100 ( 1.4%) 73 ( 1.0%) 56 (0.8%) 6,841 (100.0%) |

It must be noted that the total number of native words in the dictionary is about 30,000, most of which are compounds and derivatives listed under the main entry (cf. Fig. 42). Thus, the figure 6,841 represents the main entries excluding affixes. The European loans came, mostly indirectly through Arabic and Persian, from English, French and Russian. A survey of 100 European loans revealed only two abstract words (milwén ‘million’ and nimre ‘number’), the rest belonged to administration and objects (e.g., efser ‘officer’, polís ‘police’, caket ‘jacket’, bomba ‘bomb’, mikrob ‘microbe, germ’, istikan ‘tea glass’, lampa ‘lamp’), or miscellaneous items such as domíne ‘dominoes’, cek ‘check’, bilét ‘ticket’, etc.

The influx of loans from Arabic and Persian into Sorani has been unprecedented in the post-1918 period. This is due in part to the extension of state power over all parts of Kurdistan, which has led to (a) the provision of more schooling in Arabic and Persian, (b) the intensive use of the mass media in the two dominant languages, and (c) the disadvantaged position of the language.

The Kurdí Petí (Pure Kurdish) Movement

Purism is known to be one linguistic expression of nationalism. The divided nation and nationalism of the Kurds provides insight on the dynamism of linguistic change resulting from purism.

Purification can be traced back to the 17th century works of Ahmadi Khani and Ali Taramakhi (cf. 4.2.2 and 4.3.2.1). In his grammar of the Arabic language, Taramakhi, for example, used naw ‘name’ and gaz kirin ‘to call’ for Arabic grammatical terms ism ‘noun’ and nida ‘interjection’ (Alani 1984:57). Early journalism, too, demonstrates concern with Kurdization of borrowed letters and words. It is, however, after World War I that purification appears most strongly as a manifestation of nationalism.

The efforts of the purists of the 1920s was based on the assumption that the language had an unrecorded rich vocabulary and could be self-sufficient in meeting new needs if all the lexical resources were utilized. A reader opposed to orthographic reform wrote to Díyari Kurdistan (No. 16, 1926, p. 10) that Kurds had forgotten most of their native terms due to the frequent use of Arabic and Persian. “It is necessary,” he wrote, “to search for these unused Kurdish words and to keep our words and writing apart from those of the others so that we do not need anyone else’s terms.” A language reformer, Shaways, wrote in a special feature, “New Writing and Pure Kurdish,” in the same journal (No. 15, 1926, p. 12): “It is necessary to give the Kurdish language the color of our consciousness and spirit; we should not adorn the Kurdish language with Arabic and Persian speech but, rather, plait it richly and colorfully with the treasures of our own sweet words. ”

Language reformer Wahby believed that Kurdish was not handicapped (‘ajiz) as far as general lexical items were concerned. He found, however, that the vocabulary could not meet the demands of modern science, art and technology. In translating military instruction pamphlets for the autonomous government of Shaikh Mahmud, he replaced the Arabic terms with Kurdish counterparts as much as he could (Wahby 1973a:9-10; cf., also, 7.6.0), although the terms included large numbers of loanwords. Other writers, especially thosewriting in the press, gradually wrote in what they called Kurdi pett, i.e., ‘pure Kurdish’.

In 1926, the Kurdish Scientific Society (cf. 10.3.1) arranged a writing competition in Kurdi peti. The purpose was to make it known to the world that Kurdish was an old and orderly (rék ú pék) language not in need of other languages (Jhiyan, December 2,1926, p. 3). Soon, a “Committee for Weeding the Kurdish Language” (Komelley Bijharí Zimaní Kurdí) was formed, aimed at finding native words to replace borrowings (Jhiyan, December 9, 1926, pp. 1-2). Although the society and its committee became inactive, the Pure Kurdish movement went on uninterruptedly in both the print and broadcast media.

World War II introduced hundreds of new words and concepts into non-European languages. Although the War brought Kurdish book publishing to an end, it introduced broadcasting and one war-time propaganda journal in Iraq. The challenge of lexical innovation, exerted through the Arabic language media, was successfully met by translators, writers and broadcasters who belonged to the purist movement.

Two journals left their mark on the future development of the language. Gelawéjh, the most celebrated magazine, announced as its prime aim “weeding the Kurdish language, revival and bringing to life of Kurdish literature by protecting and collecting the old literature and by providing opportunities for publishing new literature and translating beautiful works and good foreign books” (Vol. I, No. 1, p. 2). As of May-June 1942 (Vol. 3, No. 5-6), Wahby contributed lists of Kurdish equivalents for Arabic terms and words. The editor explained that the purpose of the new section, Ferhengí Gelawéjh (Gelawéjh Dictionary), was to “give power to writing in pure Kurdish” and “to clean up the vocabulary” (Ibid., p. 94). The following examples are from Nos. 5-6, 9-10, 11-12, 1942; No.2, 1943 (Arabic loanwords are Romanized in their Kurdish pronunciation):

| Loanword | Proposed Kurdish Replacements |

| آن/an ‘time, moment’ احفاد/ehfad ‘descendants’ اختراع /ixtira’ ‘invention ‘ اقتدار/iqtidar ‘power’ اكتریت/ekseriyet ‘majority’ تجارت /ticarret ‘trade’ جزیره/cezíre ‘island’ دنیا/dinya ‘world’ زمان/zeman ‘time’ سری/sirrí ‘secret’ سعر/si’r ‘price’ تروت/serwet ‘wealth’ صلح/sulh ‘peace’ بالخاصه /bilxase ‘especially’ احصاأانفوس/ihsa ‘ulnufús ‘census’ اتحاد/ittihad ‘unity’ ادراك/idrak ‘realization’ ابدی/ebedí ‘eternal’ اقلیت/eqeliyet ‘minority’ |

kat (native) newe (native) dahénan (semantic extension) twana, yara (Persian) zorbeyeti (loan translation) bazirganí (Persian loan) dirge, durrge (dialect loan) gétí (Persian loan) dem (native) nihténé (native) nirix (Persian loan) saman (Persian loan) ashtí (native & Persian) betaybetí (native) serjhmar (calque, based on Persian) yeketí, yekgirtin (native) peypébirdin (native) cawíd(an) (Persian), nemir (native) kemayetí (loan translation) |

Two tendencies are already apparent-purifying nativized loanwords (e.g., dinya, zeman, ebedi) and de-Arabizing even by introducing new loans from Persian (cf, 8.4.2.2). Wahby and later Huzni Mukriyani contributed also to Dengí Gétí Taze which carried many articles, both original and in translation, with appended lists of neologisms. According to Wahby, the neologisms (about 1000 in 1942) were widely used by translators and purists. A contemporary observer, Edmonds (1945: 187), wrote that Wahby’s work was “consciously or unconsciously followed by writers in the other periodicals and by broadcasters on the Baghdad and Sharq-al-Adna wireless” (cf. 7.4.10.4).

Trends in Purism

As is the case in other languages, Kurdish purism has manifested conservative, moderate and extremist varieties. The success of the movement has already eliminated the conservatives who were a minority. A representative example of the conservative position is a letter quoted by Gelawéjh (Vol. 1, No. 1, 1940), in which the writer complained about confusion caused by unfamiliar neologisms and unfixed coinages (e.g., three equivalents for the Arabic loan kelime ‘word’ in one article published by the journal).

Extremism. The dominant trend has been extremism, especially since the 1960s. This extremism manifests itself in two directions. First., fully nativized Arabic loans are being purified, e.g.:

| Nativized Words | Coinages |

| qellem ‘pen’ shi’r ‘poem’ kelime ‘word’ xet ‘line’ kitéb ‘book’ nesir ‘prose’ zeman ‘time’ edeb(iyyat) ‘literature’ |

pénús honrawe, hellbest wishe héll perrtúk, perraw pexshan ‘dem, kat wéjhe |

The politics of this extremism is rooted in the conflict between Kurdish nationalism (Kurdayetí) and the two states of Iraq and Iran. ‘The Kurds of Iraq living under the direct pressure of repressive Arab governments and under the domination of the Arabic language react linguistically by purging Arabic loanwords, replacing them with new borrowings from Persian, the official language of the neighbouring, albeit equally repressive, state–Iran. Examples abound in Wahby’s lists cited above and in the most recent literature by Iraqi Kurds, e.g.:

| Persian Word | Kurdish Form |

| قشنگ/qashang ‘beautiful’ سرپرستی/sarparasti ‘ supervising’ سپاس/sipas (kardan) ‘(to) thank’ سپیده/siptdi ‘dawn پوزش/púzish ‘apology’ پزشك/pizishk ‘physician’ آمار/amar ‘statistics, census’ ورزش/varzish ‘exercise’ تندرستی/tandurustt ‘health’ |

qesheng serperishtí supas spéde pazi~ ptzíshk amar werzish tendrustí |

In the same vein, European terms are preferred to Arabic ones in the various proposed terminologies, including those of the Kurdish Academy. This anti-Arabic attitude became known in the 1980s, and the General Directorate of Kurdish Education (Beréweberétí Gishtí Xöndiní Kurdí) decreed in 1986 that foreign words and idioms (Latin, Persian and other) should be avoided and, instead, Kurdish or, if unavailable, Arabic words must be used (Bimar 1986:299).

The Iranian Kurds, on the other hand, show a tendency to purify their Persian loans by replacing them with, among others, Arabic words. For example the Persian loanword فشار /fishar ‘pressure’ is replaced by the Arabic loan zext ( ضغط/daght). Most striking is the fate of zulm, which is an Arabic word and is widely used in both Persian (zulm) and Kurdish. Because it is treated as a Persian word, Iranian Kurds tend to replace this loan with an Arabic synonym غدر/ghadr, which is rarely used in Persian. Interesting to note, the Persian loan supas (cf. Wahby’s list above), has gained acceptance among Iranian Kurds due to its naturalization and unrivalled use among Iraqi Kurds. A similar trend of anti-Turkism can be documented among the Kurds of Turkey who prefer to borrow form West European, Persian and Arabic languages. The Kurds of Iraq and Turkey usually justify their borrowings from Persian by pointing out the common “Indo-European” affiliation of the two languages. The Kurdish nationalists of Iran tend to ignore or downplay this genetic linguistic connection.

Extremism has led to the popularization of grammatically and lexically unacceptable neologisms. A well-documented case is the place-name Berrwarí, a region in Kurdistan, used as a noun, berwar, to designate ‘date’. The story is told by Zabihi (1977:61-62):

… in 1943 in the city of Tabriz, I was busy printing the [clandestine] magazine Níshtman. I had received from Syria the Kurdish newspaper Roja Nú. It carried an article under which was written “Berwarí – R.R. 1943” followed by the writer’s name. At the time, it was the habit among Iranian [Persian] writers or poets to put down at the end of their composition the word [in Persian] bi tairikhi … ‘Dated … ‘ followed by the day, month, and year of writing. Comparing the two, Berwarí and hi tarikhi matched. Without knowing that Berwarí was the name of a region … I took it for tarikh … ‘date’

Zabihi further recalled that, overjoyed with the discovery, he undertook to use the word, whether necessary or not, in whatever he printed. Unaware of its origins, Iraqi Kurds disseminated the neologism in their publications.

Opposition to extremism has occasionally been expressed in the press. Abdulla (1962: 16-20), for example, warned that Kurdish books had become unintelligible to the extent that readers found it easier to read Arabic books. He was especially critical of purging nativized Arabic loans and their replacement by Persian or European loans. The poet Hazhar (1974) argued that the purists were “molesting” (ser ú gölak shikandin= instead of “cleaning” (xawén kirdinewe) the language. Providing a detailed list (pp. 291-320) of Arabic borrowings from other languages to prove that borrowing was one legitimate source of lexical enrichment, he called for an end to purification of nativized loans. Another poet, Hemin (1983:44) castigated “the coinage of ugly, cumbersome and non-original words by the selfish and urban word-coiners (wishe datash).” Both poets were born in the villages of the Mukri region, and both are excellent prose writers and translators.

The Spoken Language. The impact of purification on the spoken and written language has been uneven. According to, Rojí Nö (Vol. 4, No.2, July 1961, pp. 38-39), the written language had been sufficiently purified, while the speech of the educated urban population carried a heavy load of Arabic. The writer warned that the influx of Arabic words was even heavier than before, especially among employees in government offices where the official language was, in practice, Arabic. In Iran, where native tongue education is not allowed, the situation is similar. Zhiyan (1972:360-61) found that Kurdish-Persian bilinguals in Mahabad used about 30% Persian and 15% Arabic and Turkish loans when they were asked to give the Kurdish equivalents of 3,000 selected Persian words.

It seems that as long as monolingual native tongue education is not available and the Kurdish reading and listening public depends on the dominant languages, this situation will continue to prevail.

The Gap Between Theory and Practice. Much of the lexical reformbefore the 1970s was carried out by individuals who were not familiar with linguistics. Kurdish grammars composed by Iraqi Kurds did not deal with word-formation, although affixation received attention for the first time in 1958. Three grammars published outside Iraq, Kurdoev (1957:293-99), McCarus (1958:82-91) and MacKenzie (1961: 140-49), had each devoted a chapter to word-formation, but it was not until the 1970s that linguistically trained native speakers began to study the subject. The first work on word-formation in Kurdish appeared in 1977 (Marit).

The reformers devoted most of their efforts to replacing loan items by “pure” words found in the speech of the illiterate native speakers. Coining was, however, inevitable, and it was done largely through the efficient method of “analogy” (qiyas) based on the coiners’ intuition and whatever linguistic insight they had gained from their knowledge of Arabic, Persian, Turkish or, occasionally, European languages.

The reformers were not aware of the dynamism of lexical change in language generally, or of the potential of the numerous morphological and semantic resources in the Kurdish language particularly. Thus, although the purists were fearless modernizers, they acted as conservatives in the innovative use of morphological features such as affixes, or in forming new derivatives or compounds not permissible “analogically.” The Kurdish Academy was apparently the first to experiment with the innovative use of grammatical features.

In 1976, the Kurdish Academy proposed the use the of verbal suffix -andin for the English -ize in verbs such as “synchronize” (e.g., heman ‘syn-‘ + kat ‘chron’ + -andin → hemankatandin) or the use of Kurdish -ekí and -etí for the English -ive and Kurdish -etí for English -ity in order to coin words such as xoyekí ‘subjective’ and xoyekíyetí ‘subjectivity’. The Academy sought legitimacy by pointing to the practice of major languages, particularly English, which has used even obsolete Latin and Greek features to expand the vocabulary (KZK 1976:9-10). There is evidence to claim that the innovations tend to be accepted. The word nirxandin ‘evaluate’ (nirx ‘price, rate, value’ + -andin ‘-ize’) is already used in non-Academy publications.

Source: Prof. A. Hassanpour, Nationalism and Language in Kurdistan 1918 – 1985